At the end of the 1930’s the Swiss Community, visualizing the world-wide political crisis that was about to take place, created the mechanism necessary to establish a secure environment in which to attract members of the private banking sector.

Its proximity to Switzerland, prompted Liechteinstein to actively participate in the task proposed by the Swiss Community. This participation included the approval of laws, which would lead to the creation of three entities, designed to allow individuals to delegate the administration of their assets to third parties, without having to reveal their identity to any governmental authority and with a level of confidentiality that was almost impenetrable. With the passing of time, these three figures developed into the Private Interest Foundation or Stiftung, as it is known in German.

Why create a new investment vehicle so similar in structure to the Trust? The need arose mainly due to the fact that the Trust had practically disappeared from the European Continent by this period. Although it is true that the Trust was an instrument that had been widely used in Europe since the Middle Ages, it was abolished during the French Revolution since it was considered an instrument used for the benefit of the Nobility to perpetually protect their assets.

As a result of Napoleon’s conquest of Europe, the ordered codification of Roman law spread, mainly within Central Europe, rendering the Trust practically non-existent and viewed as an outdated Anglo-Saxon instrument. From this point on the preference of the Foundation over the Trust in the use of structures for the protection of assets and inheritance planning began to spread throughout Europe.

As a result of the attempt to create an instrument, which would facilitate the financial operations carried out from the Swiss Community, the Liechtenstein Stiftung was born and used as a substitute for the Trust.

Liechtenstein, the Dutch Antilles, Holland, Austria and Panama, have all passed laws regulation foundations. Furthermore, traditional Common Law Trust jurisdictions such as the Bahamas are currently considering enacting laws for the creation and regulation of Foundations.

Foundations have also been recognized by courts in countries such as The United States, England, Canada and Australia, adding in turn credibility to its structure and operation, and confirming that any revision that is made to its structure should be adjusted to the law of the jurisdiction where it originated.

ADVANTAGES OF THE FOUNDATION

When the name “Foundation” is mentioned one almost immediately thinks of the traditional non-profit organizations, whose purpose is wholly charitable and which is used primarily in the interests of social welfare. The Foundation of Private Interest, however, does not have any connection with the traditional foundation. The structure of a Stiftung or Foundation is more closely related to and inspired by that of the Trust, but also implement certain advantages and key elements from a corporate structure.

Simply and straightforwardly, the Foundation constitutes a hybrid between a Trust and a Company and thus combines the most favorable aspects of each. It may be used as a more efficient and versatile instrument for the management of banks accounts, as a means of effecting transactions on the stock market, as a holding vehicle of subsidiary companies, to control and exercise the rights of shareholders, to own real property and for family inheritance planning, among other things.

If we had to choose three words to describe the benefits that a Foundation offers, those would be confidentiality, protection and control. Confidentiality because the Foundation allows the investor to perform transactions and investments and to distribute the proceeds generated from the same, with a grade of impenetrability superior to that offered by any other type of investment instrument. Protection, because the most laws regulation foundations but more so the Panamanian legislation regulating Foundations, confer upon the Foundation excellent mechanism for the protection of the same against third party claims. Finally, control because its flexibility allows it to be organized in a way in which the Founder can take charge of its administration and operation at his or her discretion. In the case of Panamanian Foundations, all of the above may be accomplished in a tax-exempt environment.

As compared to the Anglo-Saxon Trust, the Foundation boasts, as its most outstanding advantages, the following:

The law allows the Founder to exercise a greater amount of control over the administration and organization of the foundation and the assets belonging to the same, than that which the Settler is permitted to exercise over the assets pertaining to a Trust.

The Foundation is a legal entity with full capacity to represent itself before third parties. As such, all assets, which are transferred to it, will be registered in its name, in a way that is similar to the transfer of assets to a company. The Trust, on the other hand lacks legal personality. As such, the Settler owns the Trust assets. In the case where the Settler wishes to appoint a new administrator, he his required to begin the complex and cumbersome process of transferring assets from one Trust to another, which besides its complexity, can create tax consequences. In the case of the Foundation, the same is achieved by the removal of the members of the Foundation Council, which is effected with the same simplicity as a change of the Board of Directors of a company.

The requirements of the law regulating Panamanian Private Interest Foundations allows for the maintenance of a completely confidential record of the identity of the beneficiaries of the Foundation, and the way in that the assets are to be distributed. In the case of a Trust, the identity of the beneficiaries must be recorded in the Trust documents. The one exception would be a Discretionary Trust, which creates then for the Settler a concern about the transmission of the Trust assets to his intended beneficiaries.

Panama Private Interest Foundations expressly allows the Founder to appoint a Protector as the body/individual in a charge of supervising the activities of the Foundations assets. Many of the laws from other jurisdictions that regulate Trusts do not include the Protector or similar figure.

The Private Interest Foundation offers more security and reliability than the Trust. The Anglo-Saxon Trust has been and is frequently declared void by the courts of Anglo-Saxon jurisdictions. Most of the these decisions have been motivated as a result of the situation where the Settler has retained too much control over the management of the Trust Assets, whether in a direct and discernible way or through advisors and intermediaries. In such cases the courts have viewed the Trust as a façade, in that the assets were never effectively transferred to the Trustee. On other occasions, decisions of Anglo-Saxon courts have led to the Trust being found void where the beneficiary and not the Settler was actually controlling the administration of the Trust assets.

In the case of the Panamanian Private Interest Foundation these problems are avoided. The Private Interest Foundation acquires legal personality from the moment of its registration in the Public Registry. Its validity as of that moment cannot be contested because the governing legislation guarantees clearly and unequivocally that the Founder or Protector, and not only the Foundation Council, may exercise control over the Council and thus over the activities of the Foundation. Furthermore, the Panamanian Courts that has jurisdiction to resolve controversies that arise in relation to the operation or structure of the Foundation lack the ability to legislate on the same, as the law is based on the traditional Roman Law system. Such is not the case in the Anglo-Saxon court system, which frequently surprise Trustees and frustrate the intentions of Settlers by voiding Trusts based on ever changing considerations.

Another advantage of the Foundation is reflected in the special protection guaranteed to the Foundation Assets. Like a Trust, the Foundation assets constitute capital that is separate from the assets of the Founder and as such cannot be attached by creditors or third parties. Panamanian Foundation law, however, has adopted even more stringent asset protection features. It provides that transfer of assets to a Foundation may not be affected, after a period of three years from the date of transfer. This has the effect of preventing any creditor or third party from even so much as bringing a claim against the Foundation in an attempt to impede the transfer of assets to the same after the expiration of such period.

One important advantage gained by using a Panamanian Foundation is its tax treatment. For tax purposes, Foundations receive de same treatment as an offshore Panamanian company, and as such, is governed and benefits from the Panamanian tax principle of territoriality. Under this system only income or profits generated within the geographic territory of Panama are subject to tax. Any profit obtained from activities outside of Panama, such transfer or acquisition of securities, management of banks accounts and investments, the transfer or sale of real property or chattels, and the dividends received from companies operating abroad, will be exonerated from Panamanian taxes.

Notwithstanding, Panamanian Foundations not only benefit from the territoriality principle already referred to. The law governing Panamanian Foundations, in a way to confirm the principles of Panamanian tax laws, also establishes a specific exemption with respect to the transfer of property to the Foundation and payments made to beneficiaries of the same, as long as such payments are made in connection with:

Property located outside of Panama.

Money deposited the income of which does not pertain to a Panamanian source, or when its income is not taxable in Panama for whatever reason, regardless of where such money is deposited.

Shares or securities of whatever class, issued by companies, whose income is not derived from a Panamanian source or when its income is not taxable for any reason, even where such assets or securities are deposited in the Republic of Panama. Foundations may be useful vehicles then, in lieu of offshore holding companies.

The law regulating Panamanian Private Interest Foundation goes further still. It exonerates from any form of tax those transfers of property located in Panama, where there is a first-degree kinship between the party transferring the property to the Foundation and the beneficiary.

There is not doubt that these fiscal advantages extend and complement the numerous benefits that are offered by the Foundation.

ANATOMY OF A TYPICAL FOUNDATION

The Foundation Charter and the Foundation by-laws are the two important components of a Foundation of Private Interest. In particular, Panamanian Foundation Law is quite flexible in the requirements it imposes in each of them. A brief explanation follows.

1. The Foundation Charter.

The Foundation Charter can be viewed as the equivalent to the Articles of Incorporation of a Company. Said document contains an operational framework of the Foundation.

Panamanian Foundation law does set some basic requirements for the Foundation Charter. Accordingly, each Foundation Charter must include at least: the name of the Foundation, its initial capital which in no case may be less than US$10,000.00, the identities of the Council members, its domicile, the name and domicile of its resident agent, the purpose for its creation, the manner of appointing its beneficiaries, its duration and the destination and distribution of its corpus if the Foundation is dissolved. It may also include the powers that each entity of the Foundation will have, the manner in which they will approve their decisions and will be chosen, and the times at which such elections will be made. Panamanian Law requires that the Foundation Charter be recorded in the Public Registry to become a legal entity.

2. The By-laws.

The by-laws constitute a private and confidential document that complements the Foundation Charter. It does not require registration with any Registry or authority. As such it will not be available for inspection through the Registry or any other means. The by-laws contain the names of the beneficiaries and establish the way and the proportion in which the assets and income of the Foundation will be distributed to the beneficiaries.

The by-laws may also contain any other stipulations regarding the operation of the Foundation that has not been included in the Foundation Charter.

Most Foundation laws and particularly Panamanian law on Private Foundations, do not contain restrictions or limitations other than those outlined for the Foundation Charter, with respect to the contents of either document. Thus, either document can be structured according to the needs of the Founder.

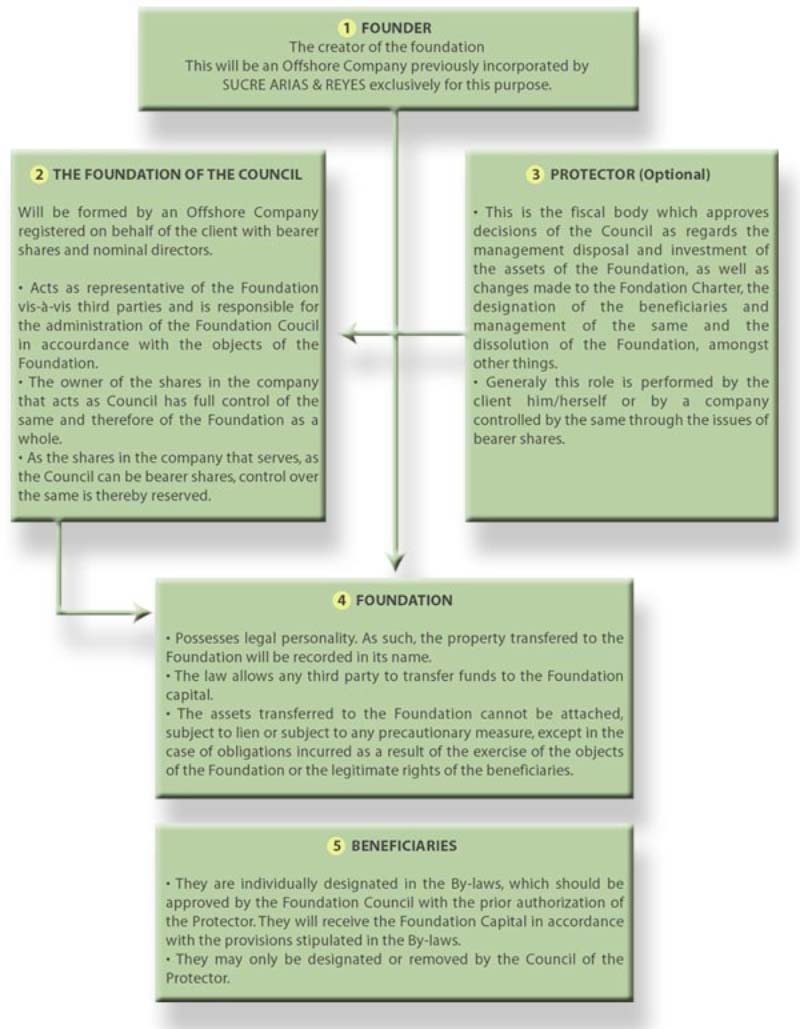

Foundations are comprised of three key entities: The Founder, the Foundation Council and the Beneficiaries. There also exists a fourth, albeit optional figure: The Protector.

3. The Founder.

The Founder is the person in charge of the organization and creation of the Foundation and is the equivalent of a Settler in the case of a Trust.

To guarantee that the identity of the Founder is preserved, Panamanian law is flexible enough that a nominee Founder may be appointed. In such a case, the Foundation Charter will be drafted to assign all controlling authorities and decision-making capabilities to the Foundation Council, the Protector or both, and none to the Founder. Since Panamanian law authorizes transfers to the Foundation by third parties, the client can then transfer his or her assets once he or she is content that the Foundation Charter does assign the control exclusively to the Council, the Protector or both. The client can then be appointed in either capacity. Please see point one of the attached diagram.

4. The Foundation Council.

Each Foundation requires a Foundation Council that will be in charge of overseeing the fulfillment of the Foundation objectives. Said Council, in its operational form, can be compared to the Board of Directors of a Company. The Council is in charge of the administration of the assets of the Foundation and can enter into any acts, contracts or other legal business convenient or necessary to the purposes of the Foundation, while always observing the limitations imposed by the Foundation Charter.

The Panamanian Foundation Council can be comprised of individuals or legal entities. In the case of individuals, the minimum number of members is three. In the case of a Company or legal entity of any other fashion, only one member is required. Please see point two of the attached diagram.

If combined, the use of nominee Council members and the Protector, or the use of a Company issuing bearer shares in either capacity, will allow a client to retain control over the Foundation, while ensuring a reserve of himself or any individuals that actually exercise said control.

Hence, a Panamanian Foundation Charter may be structured in such a way that decisions related to the sale or disposition of the assets of the Foundation, such as the investment of the same, will have to be adopted by resolution of the Council with the prior approval of the Protector. The Council with the prior approval of the Protector makes other important decisions, such as the designation of new beneficiaries or their replacement, amendments to the Foundation Charter and the by-laws, and the dissolution of the Foundation.

2. The Beneficiaries.

The beneficiaries of the Foundation are limited to receiving the income and assets of the Foundation and do not possess any further rights other than those established in the Foundation Charter or in the by-laws. The designation of individual beneficiaries and any details of the way that assets will be distributed to them may be stated in the by-laws. The identity of the beneficiaries is kept strictly confidential, in that the by-laws are a private document that does no require registration before any Registrar or governmental entity.

Both individuals and Companies may be appointed as beneficiaries of a Panamanian Foundation of Private Interest. Please see point five of the attached diagram.

Based on the foregoing qualities, the Foundation of Private Interest must be considered as a reliable, flexible and discreet instrument, ideal for use as a vehicle through which to channel investments and accumulate and organize controlling shares of subsidiary companies with minimal or not tax liability, while at the same time protecting them from third party claims and distributing them in accordance with the estate, financial wishes of the Founder.

Without doubt, no offshore estate planning or corporate holding scheme may be complete if it does not consider at the top of its list the use of a Foundation of Private Interest.